Only recorded duel in Panola County

Published 2:25 pm Friday, February 28, 2020

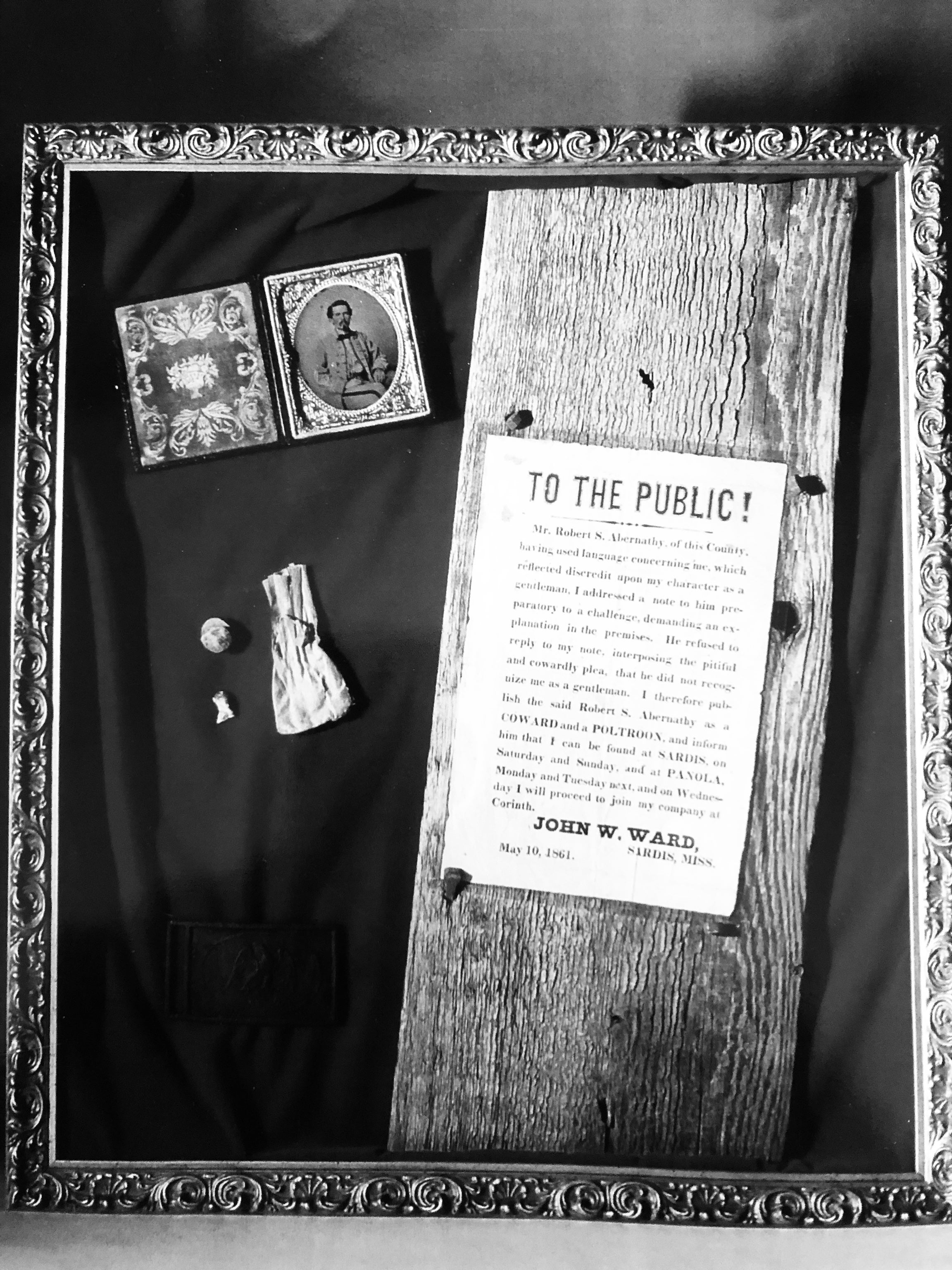

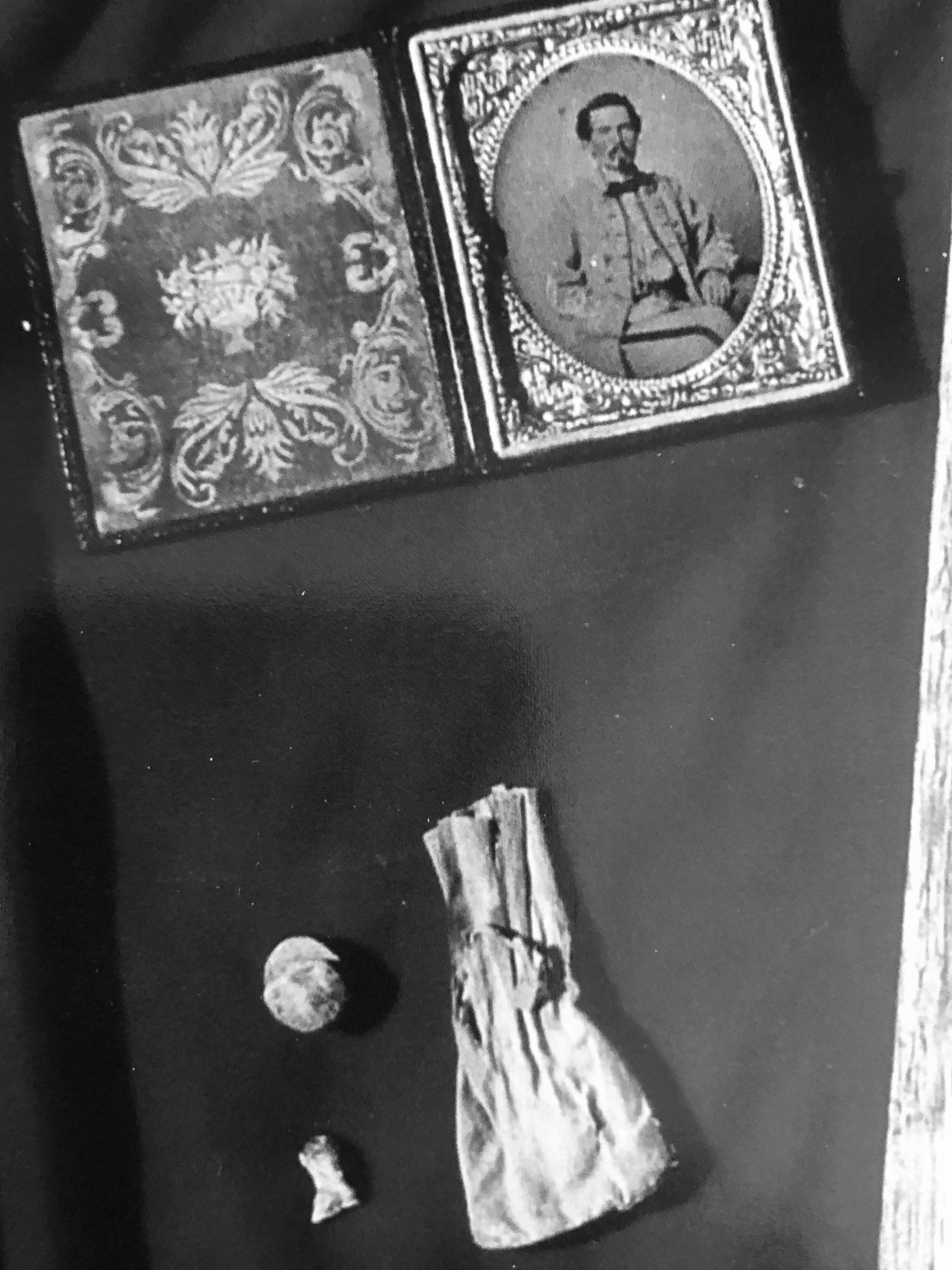

A Civil War artifacts collector in California has the original broadsheet posted in Sardis and Panola in 1861 that led to the duel, along with a photo of John W. Ward and his memorabilia from the event that nearly killed him.

Local history enthusiasts recently heard a presentation that outlined the few details of the only recorded duel fought in Panola County, including information about the men involved in the affair.

John Nelson spoke about the 1861 duel at a recent meeting of the Panola County Historical and Genealogical Society.

Nelson, perhaps the leading authority on the history of Batesville and Panola County, said he was unaware of the duel until a collector of Civil War artifacts and memorabilia from California contacted him for more information about the men from Panola County involved in the fight.

“In all of my research this duel had never come up, which was not unusual considering that dueling was illegal and not nearly as common as I had thought before I began my research,” Nelson said.

He said the fact that a collector from California is now is possession of the few remaining pieces of evidence from the duel is disheartening to local historians, who wish such items with local connections could be kept in private collections, or maybe a museum, instead of finding homes in other states, likely never to be returned to Panola County.

Nelson has read every issue of the old Panola Star newspaper on file and all of The Panolian editions, besides hundreds of other pieces of written history, including diaries, pages of notes, and other publications. Nowhere, he said, was the duel mentioned. His research helps to fill the gaps and provides a glimpse into the county’s history.

The story of the duel begins with a flyer – then called a broadsheet – that was printed and posted around the towns of Sardis and Panola (now Batesville). The protagonist would not have published the flyer as a newspaper advertisement for the same reason the local whiskey bootleggers would not, because participating in a duel was an illegal activity.

Actually, Nelson noted, by the 1850s dueling seemed to have fallen out of favor in the South, and was not the romanticized affair of gentlemen settling their differences with the blessing of their families, friends, and the local sheriff often portrayed in books and movies.

Most Americans, in the North and South, had opposed duels since 1804 when Vice President Aaron Burr killed a political rival, former Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton, at Weehawken, N.J.

Burr, in fact, was charged with murder and had to escape to the South to avoid prosecution. The charges were eventually dropped and he returned to Washington, D.C., to finish his term as Vice President.

This duel, then, was probably a rare event for Panola County, although run-of-the-mill shootouts were just as common in that era as they are now.

The inflammatory broadsheet read as follows:

TO THE PUBLIC:

Mr. Robert S. Abernathy, of this County, having used language concerning me, which reflected discredit upon my character as a gentleman, I addressed a note to him preparatory to a challenge, demanding an explanation in the premises. He refused to reply to my note, interposing the pitiful and cowardly plea, that he did not recognize me as a gentleman. I therefore publish the said Robert S. Abernathy as a COWARD and a POLTROON, and inform him that I can be found at SARDIS, on Saturday and Sunday, and at PANOLA, Monday and Tuesday next, and on Wednesday I will proceed to join my company at Corinth.

s/ JOHN W. WARD

Sardis, Miss.

May 10, 1861

Apparently, Ward thought he would have the duel and then report with his company to Corinth where troops from all over the South were preparing to gather and assemble under the military umbrella of the Confederate States of America.

The aggrieved Ward was a 2nd Lieutenant of the Sardis Blues that became Company E of the 12th Mississippi Infantry Regiment.

His counterpart, who had property in what is now the Terza community, was Captain of the Springport Invincibles, who became Company G of the 19th Mississippi Infantry Regiment.

No one knows the exact date the duel was fought, or even the location. It presumably occurred around Sardis, and there are no known records of communication between the two parties prior to the actual duel.

Readers will remember that duels were often drawn out affairs with each party naming “seconds” to stand in for them and often taking weeks of letters back and forth laying out the ground rules of the proposed duel.

It was during this pre-duel period that many arguments would essentially be settled with the participants informally agreeing they would not “shoot to kill” during the duel, and would sometimes intentionally shoot past their opponent.

No such agreement was reached in the Panola County duel, and when the dust had cleared Ward lay on the ground bleeding from a head wound.

He did not die, but in fact recovered rather quickly and was able to join his assigned regiment – as did Abernathy – to begin his service as an officer in the Confederate Army.

Among the artifacts now owned by the California collector is the .50 caliber ball of lead and a small piece of Ward’s skull that he put in a small pouch and tied around his neck when he left Panola County to fight in the Civil War, a personal talisman it seems.

Nelson tracked down a few mentions of both men’s service during the great war, and has been able to place each of them at various battles, although it doesn’t appear the men were ever in the same conflicts throughout the war.

Ward sent a report to the Panola Star in June, 1862, stating that 24 of his 46 men had been killed or wounded. Also that month, the 12th and 19th Regiments were combined to form the 2nd Miss. Brigade, under the command of W.S. Featherstone.

In September of 1862, Abernathy sent a dispatch of “all safe in my command” after the 2nd Battle of Manassas. On the last day of 1862, Abernathy sent a letter to the Secretary of War resigning from the Confederate Army and is thought to have returned to Panola County shortly afterwards.

Ward led Company E into the Battle of Chancellorsville in early May, 1863, and took a bullet in the head, almost two years exactly since his head wound suffered during the duel with Abernathy.

Remarkably, he survived again, although he was left with a paralyzed left leg and other complications. He spent months in a Richmond hospital before being returned home to Sardis.

Not content to sit out the remainder of the war, Ward transferred into the Invalid Corps on May 13, 1864, where he served as a recruiting officer in Sardis. Members of the Invalid Corps were injured veterans who were accepted back into service (in both the Northern and Southern armies) with various duties, including guarding prisoners of war, changing bandages, and a myriad of war-related activities.

Records show that Ward made a trip to Memphis in 1865 to officially surrender to federal marshals, where he received a parole as a former military combatant of the United States.

Abernathy died just a few years after the war, in 1871. He is believed to be buried, along with his wife Ann Fisher Dickens, at Terza, but no tombstone has been located.

Ward died in 1905 and is buried at Greenville in a marked grave with a headstone. Nelson said his research indicates that Ward had a successful business career in Panola County, but there is nothing to indicate why he had moved to Greenville at the time of his death.